I’m pleased to announce that I have been commissioned by the Harlow Art Trust to undertake a virtual residency at the Gibberd Gallery, Harlow, culminating in an online interactive art work to launch in November 2016. The commissioning strand is called ‘reframe’ and I’ll be posting thoughts using the tag ‘reframe’ until as and when I think of a better name for the final work! Essentially, I’ve been asked to ‘reflect, challenge and celebrate the Harlow aesthetic, its post-war collections and the unique and utopian New Town values.’

Having been over to Harlow only briefly to discuss the commission with staff at the Gibberd, I thought I would visit today purely to get my ‘feet on the ground’ and find out a bit more about the way the town as it is came into being.

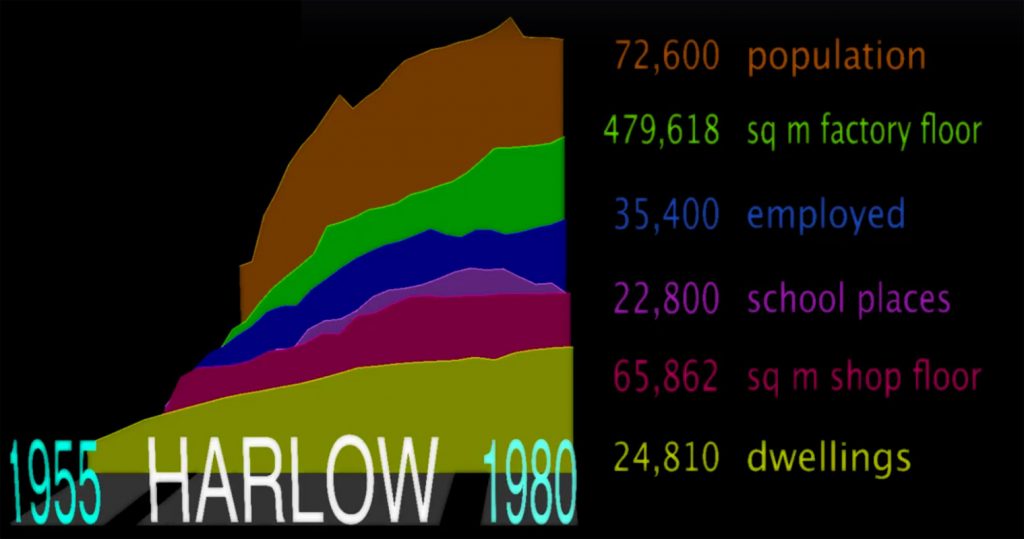

Harlow was one of the ring of new towns built around London in the aftermath of the Second World War when strategic planners attempted to cater for and manage population growth and movement rather than let it expand organically. Harlow was unique among the designated development areas in that its original population was particularly low at 4,500 being chiefly dispersed between small hamlets and villages. Perhaps this unique situation was thought of as a particularly ‘blank canvas’ by town planners led by Frederick Gibberd, namesake and forefather of the Gibberd Gallery.

“The design of a town – like the design of a car – is based on function. It has to work smoothly and efficiently. But, as with a car, we like a town to give pleasure to the eye, to be beautiful. So the history of Harlow’s design is also concerned with art, with the imagination that has been put into soving the practical problems.” Frederick Gibberd, quoted in ‘Harlow the Story of a New Town’, 1980.

The process of creating a new town such as Harlow was certainly imbued with idealism. It had to be as there were no immediate comparable precedents that had proved succesful although the earlier Garden City Movement was certainly an influence. The pre-war development of new housing estates outside of London, such as at Dagenham, was seen as problematic due to lack of local infrastructure and employment opportunities. Conversely, the post-war development strategy was to create self-sufficient, self-employing new towns that would attract industry and be able to provide for themselves.

It seems unthinkable now that central government would have the audacity, let alone the political will, to commission the planning and development of new towns designed for 70,000+ inhabitants on green field sites.

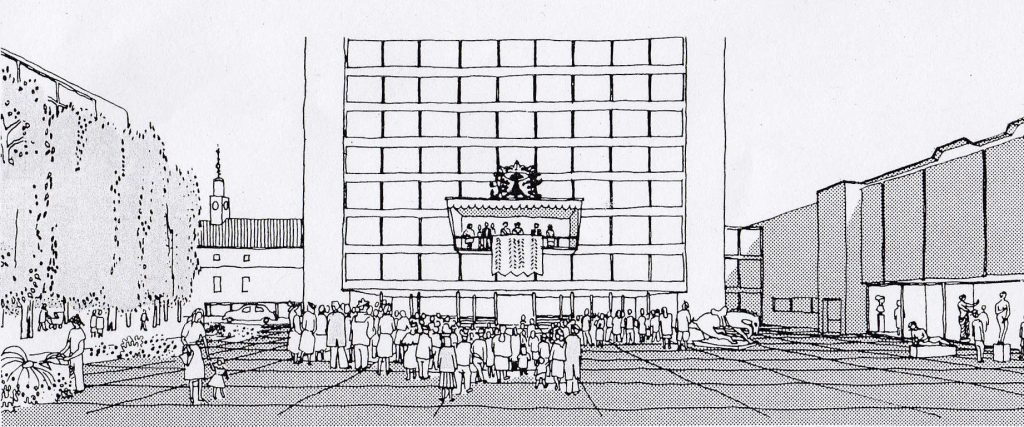

1947 sketch imagining civic life in the future new town of Harlow.

1947 sketch imagining civic life in the future new town of Harlow.

Harlow today showing part of the cast bronze sculpture ‘Trigon’ (1961) by Lynn Chadwick.

Harlow today showing part of the cast bronze sculpture ‘Trigon’ (1961) by Lynn Chadwick.