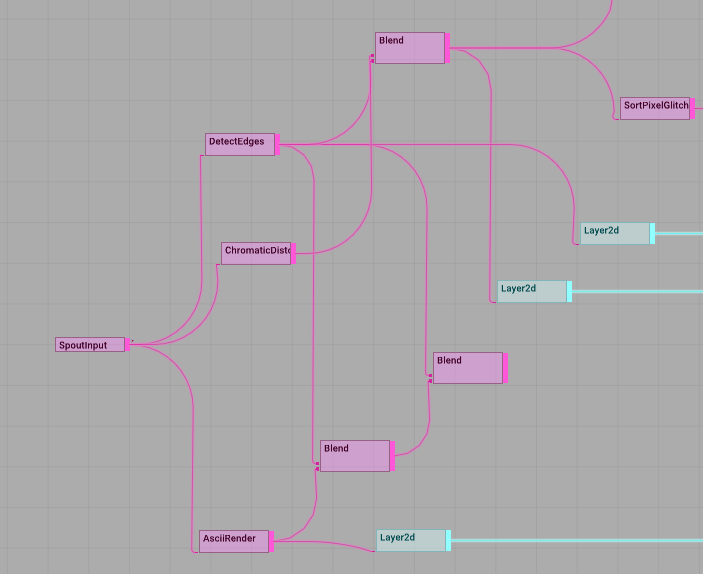

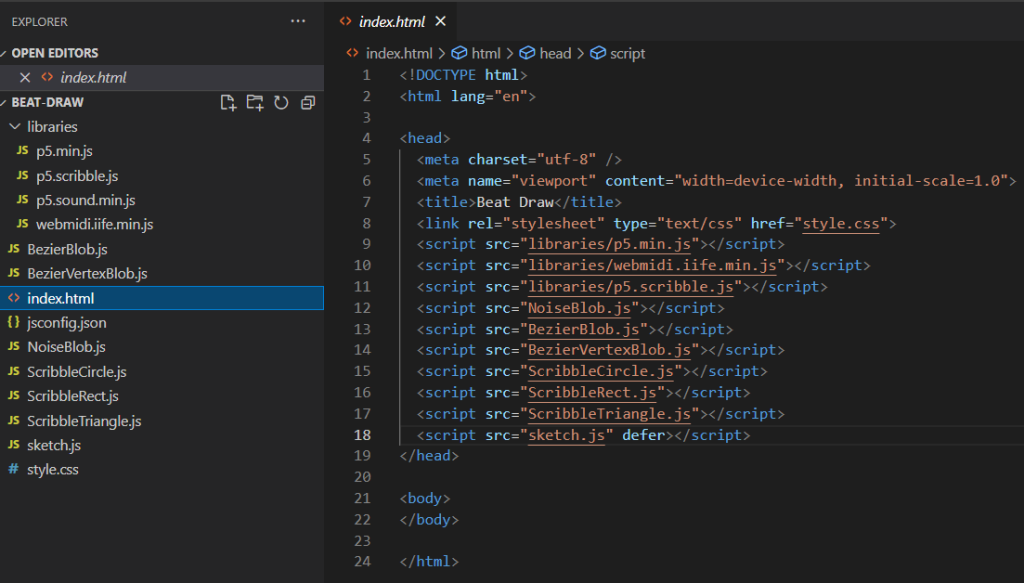

Recently I’ve been building on the performable landscapes techniques that I developed using TouchDesigner last year. In fact I gave a short presentation at a recent TD event in London, the first official event of its kind in the UK, which was fun, even if my presentation didn’t go quite to plan!

My motivation is to create a palette of landscapes that respond to musical information in realtime, i.e. MIDI and volume data, so that I can focus on playing the music and the visualisation just takes care of itself. Here are a few of the landscapes that have inspired me:

The English Lake District, a place close to my heart since childhood. Note the rounded and humped-back shapes of the hills in this view.

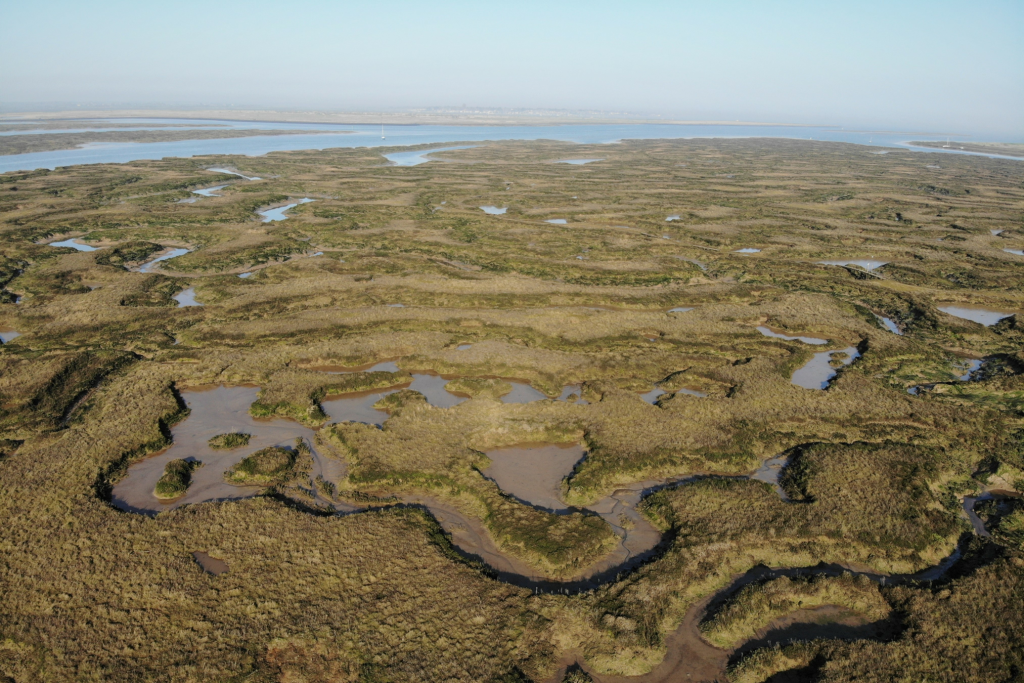

Salt marshes at Tollesbury, on the river Blackwater in Essex, an area I also know well. Note the incredibly circuitous channels of water cutting through the marsh.

Low lying rocky islands, part of an archipeligo along the West coast of Sweden. Note the predominantly grey colour palette of this scene.

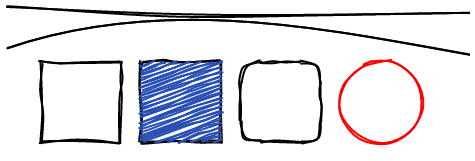

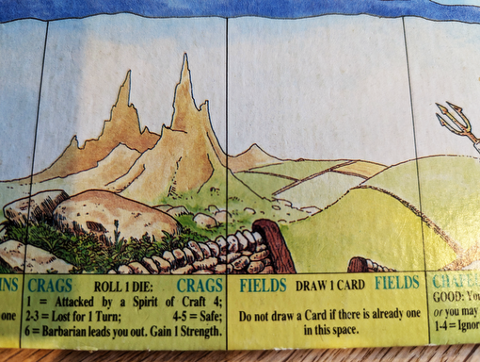

I’m also inspired by hand-painted representations of landscapes and terrain. The Talisman board game has rather endearing representations of landscapes such as the fields and crags spaces shown here. I’ve been playing this game off and on for many years so perhaps the appeal is based on nostalgia 😉

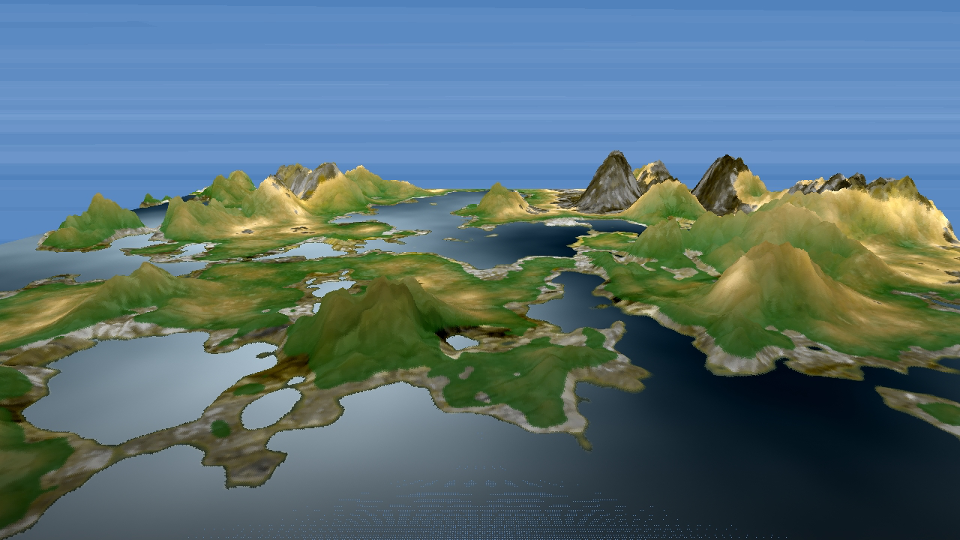

In TD it’s easy to create a simple landscape by rendering the Noise TOP in 3D (more on how to do this below). Note the characteristics of the Noise TOP as shown in the parameters dialogue on the right.

Here’s another Noise TOP with different characteristics.

By combining these TOPs using a Composite TOP, a more complex landscape can be created. In this case the Multiply blend mode is used, but other blend modes also work and provide differing results.

This is the basic rendering approach, a grid is used to generate points. Noise values are used to control the PBR material.

The classic approach to adding colour based on height is to take an output from the main noise TOP, invert it using a Level TOP and then feed that into a Lookup TOP which also has a Ramp TOP feeding it.

I have taken this a step further by using Threshold TOPs to isolate individual height bands and add a texture such as water or rock to certain parts of the final image sent to the PBR material’s Base Color Map parameter.

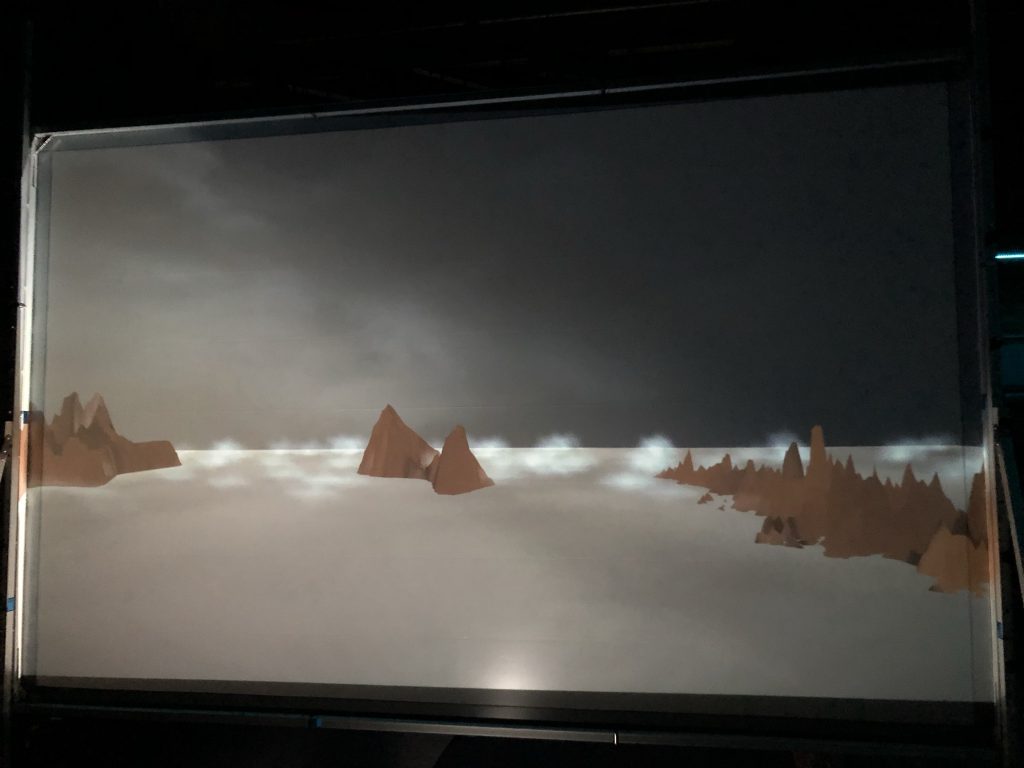

Here’s an example of a landscape using the techniques described above.

GLSL

I have more recently optimised this process using GLSL shaders to replace both the double noise technique and ramp/threshold/texture combination.

If you’re interested in learning how to write a landscape shader for TD, check out Part 1: Procedural Terrain Generation in TouchDesigner by Lake Heckaman.

MIDI

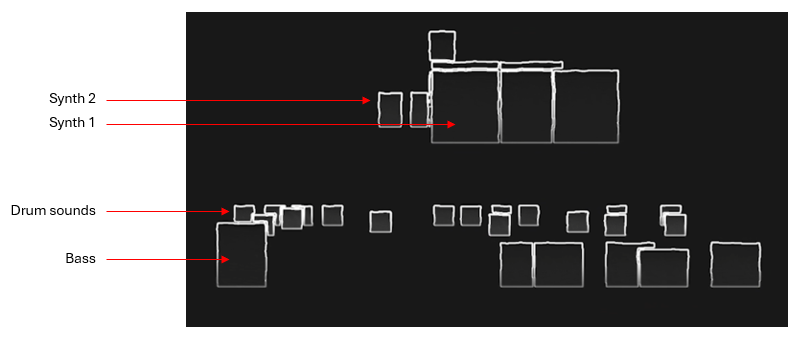

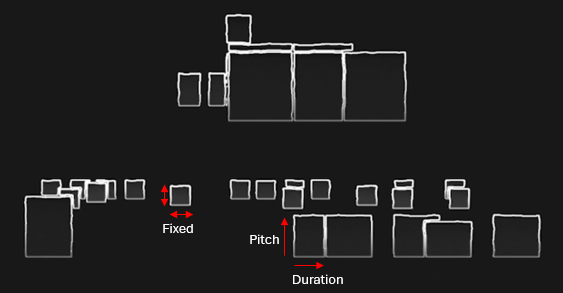

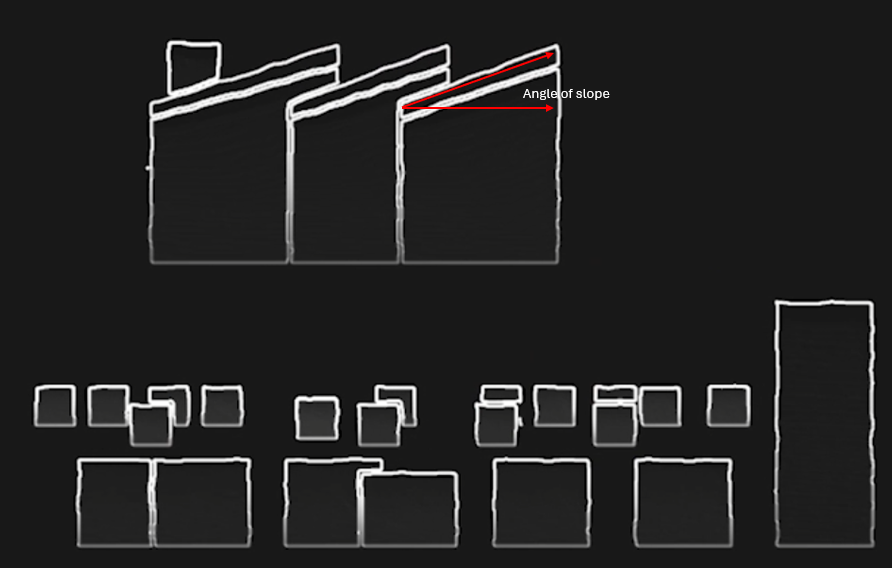

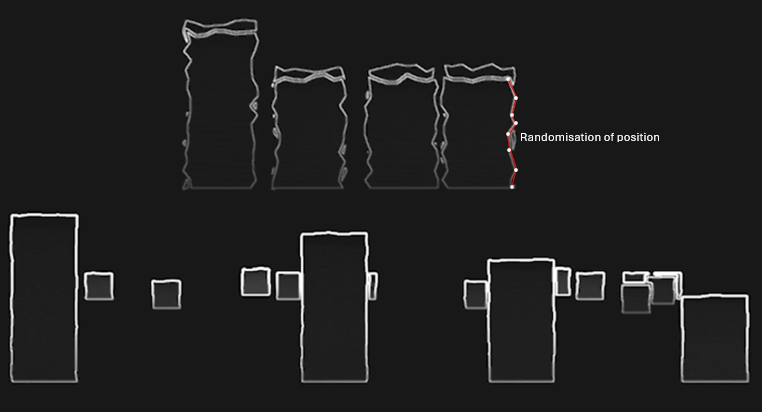

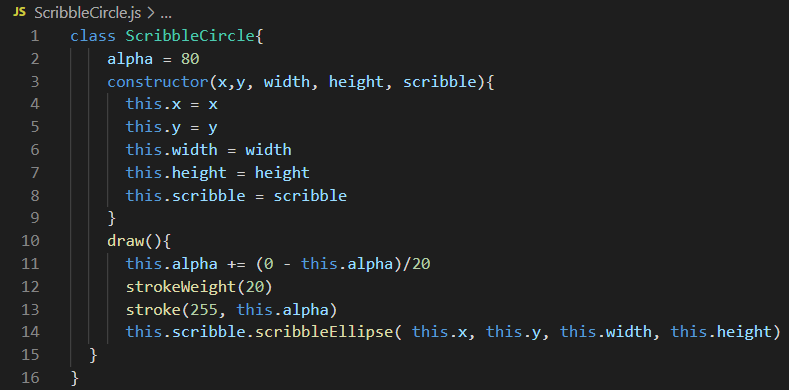

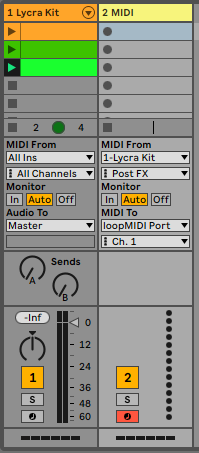

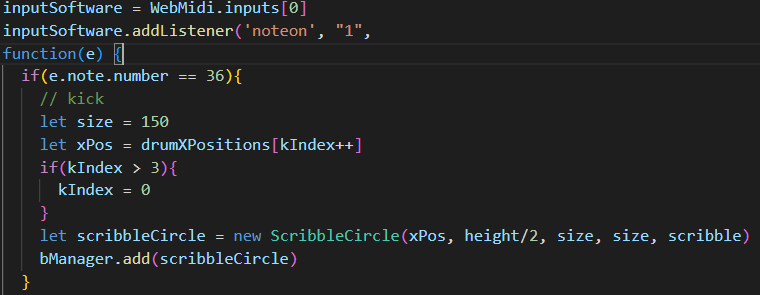

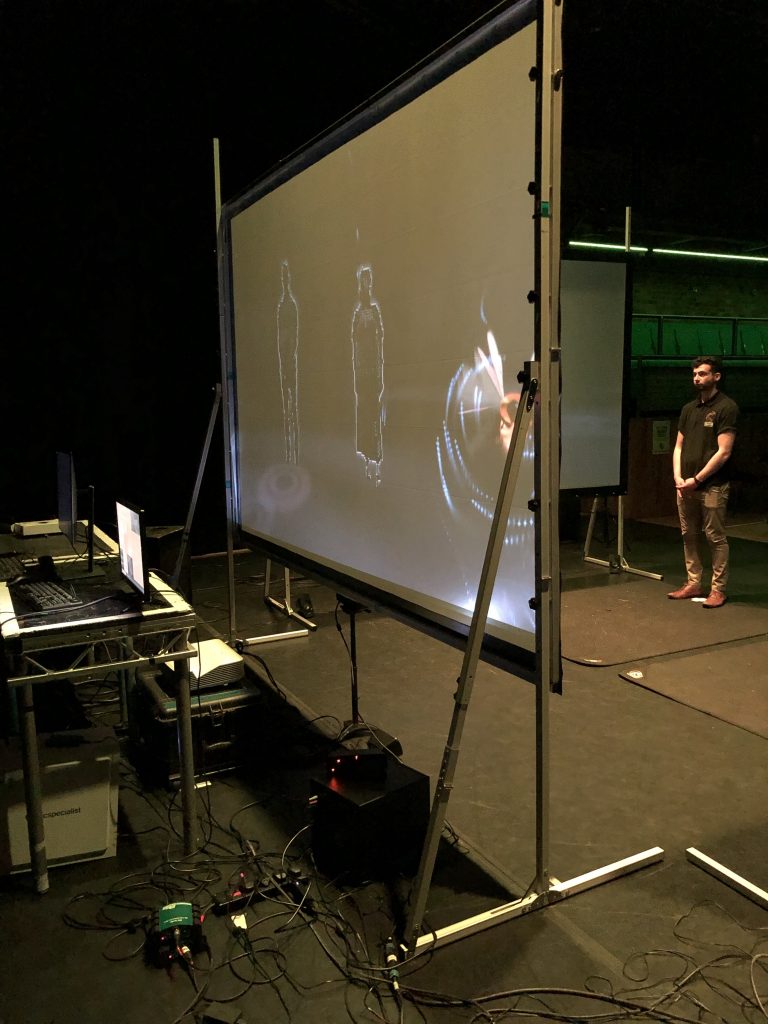

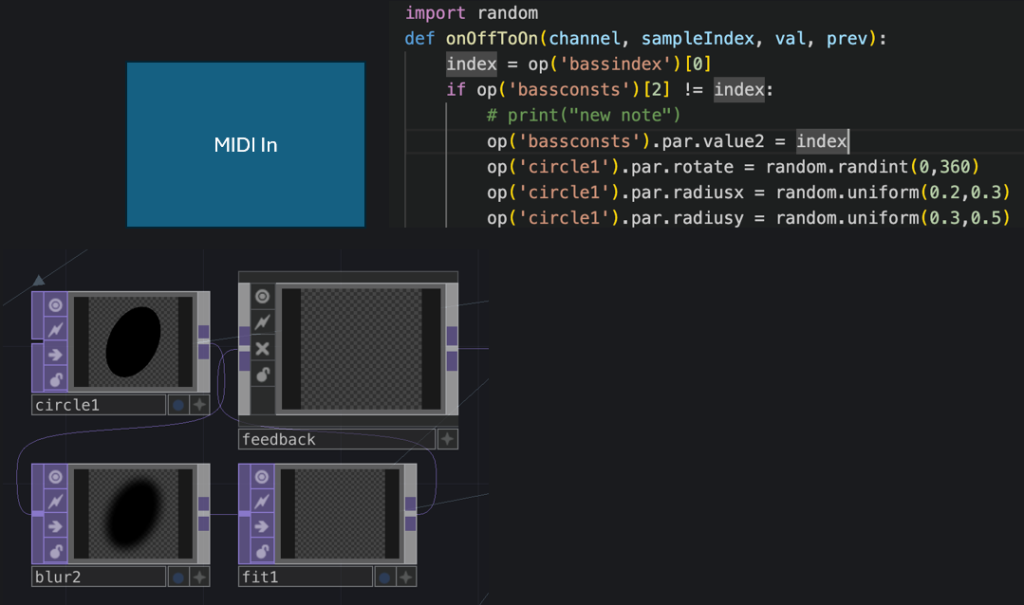

I’m using my trusty Roland Sh4D synthesiser which provides 5 separate channels of audio + the usual MIDI data over USB. This is great as I can use a combination of MIDI note, MIDI controller and channel volume level to affect the terrain. The image below shows how incoming MIDI from one of the bass channels is used to postion a deformed circle over the main noise image. If the circle was black, as shown below, it would cause a pool of water to be added to terrain at the given point. However, I have since changed this to create a hill or elavated area by changing the colour of the circle to white. The lighter the image pixels in the main noise image, the higher the terrain is rendered out as.

Audio

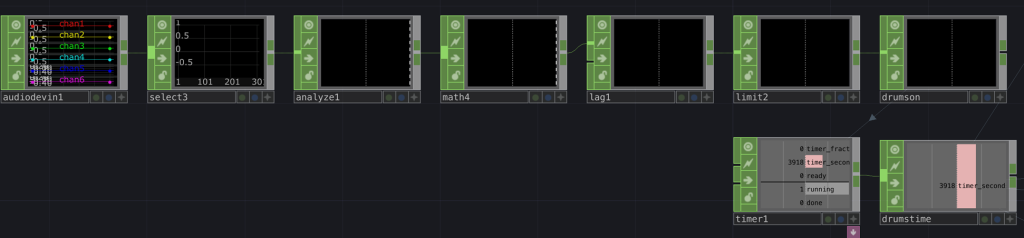

One challenge has been to create a clock that runs only when the drums are playing. I solved this by selecting the drums audio channel, using an Analyze CHOP to monitor the RMS level of the drums, which is always positive, attenuating the signal with a Math CHOP (multiplying it in this case), adding a Lag CHOP so the signal doesn’t shut off too quickly, and then passing this through a Limit CHOP set to ceiling. The net output is 0 or 1 representing when the drums are playing or not. I then connect this to a Timer CHOP which creates an accumulating value that stops and starts with the drums. I use this to drive all of the scrolling animations.

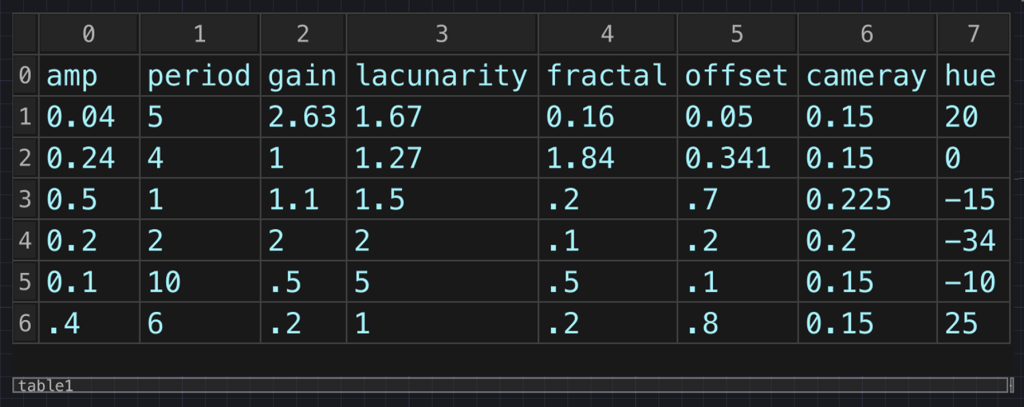

Next up, rather than tweaking every parameter in realtime and sometimes hitting on a good combination and sometimes not, I created a table that stores the values of a number of presets. This is super useful as I store all of the primary noise parameters that define each terrain preset + additional information such as camera y position, which changes slightly according to how high the preset extends. I also use the current index to control the choice of colour Ramp TOP and texture set-up per preset.

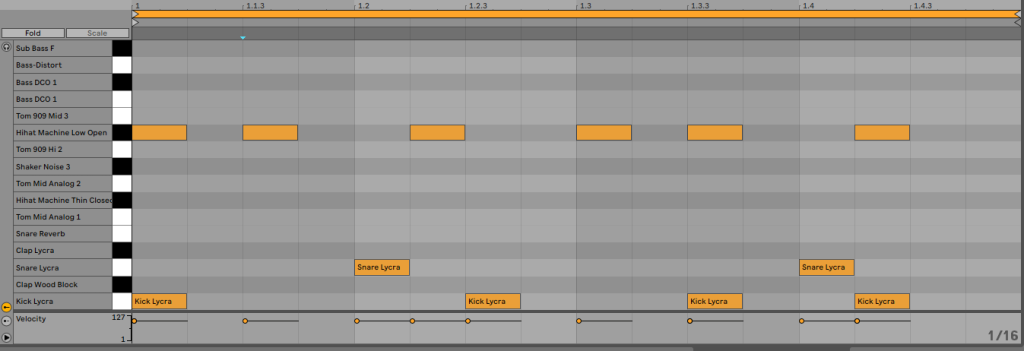

Finally, I had been testing the presets using number keys, but I decided to make the preset change at random every so many bars. This is achieved by simply having a drum note that doesn’t make any sound at the beginning of a bar. Although the drum is silent, it still sends a MIDI signal which is used to trigger the preset change.

There are various other embellishments I have made and many more I would like to make, but I feel that I need to draw a line under the project, at least for now. Here’s a video excerpt of the performable landscape in action.