I’ve recently returned from the Nineteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction (TEI’25) hosted by Université Bordeaux. This was my first experience of TEI and it was really insightful and encouraging to meet and hear from international researchers and creative practitioners at the forefront of tangible interaction in its many forms. This annual conference is essentially an international community of talented makers keen to constructively critique one another’s research and practice.

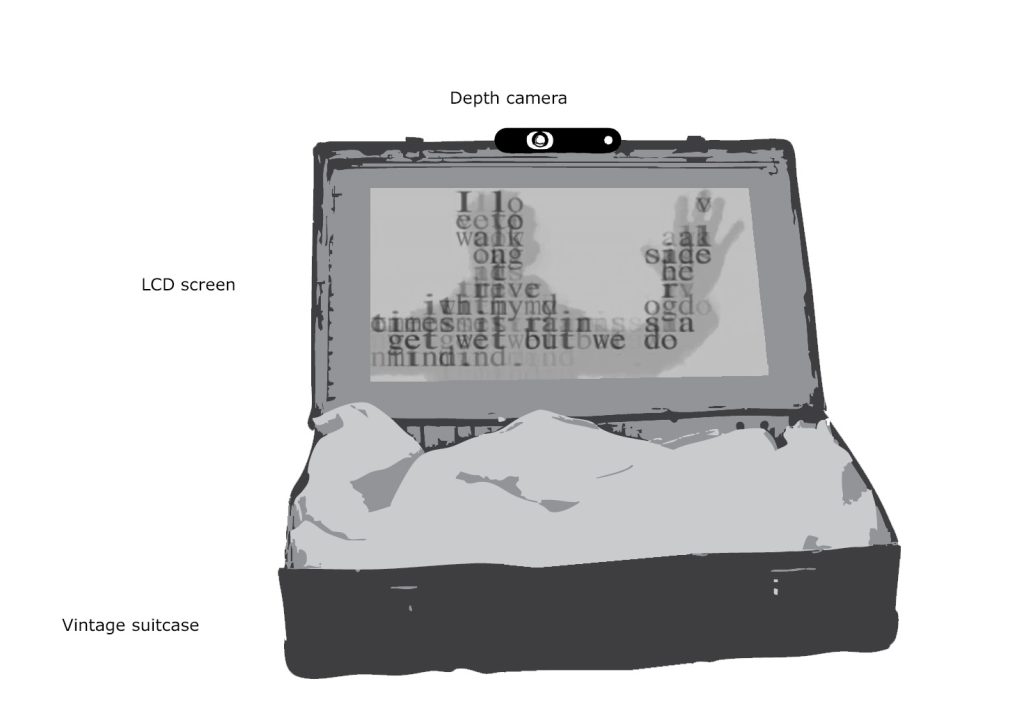

I was very happy to show an installation ‘Suitcase Stories’ which was included as part of the conference Arts and Perfomance track, exhibiting at Capc Contemporary Art Museum Bordeaux. I proposed Suitcase Stories in response to the Art and Performance call which asked artists to propose an art work fitting into a suitcase, somewhat inspired by La Boîte-en-Valise [Box in a Suitcase] by Marcel Duchamp, also responding to the conference theme of sustainability.

A number of themes I had previously been considering fed into the ideation process. Firstly, the 17 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, many of which are concerned with improving social and personal factors, not just developing infrastructure, although these aspects are evidently interrelated. Secondly, lived experience and personal testimony of climate change – I personally find first hand accounts of subjects such as flooding and drought very moving. Thirdly, bodily interaction with typography as a way to develop a near-physical relationship with narrative.

This led me to develop the following proposal:

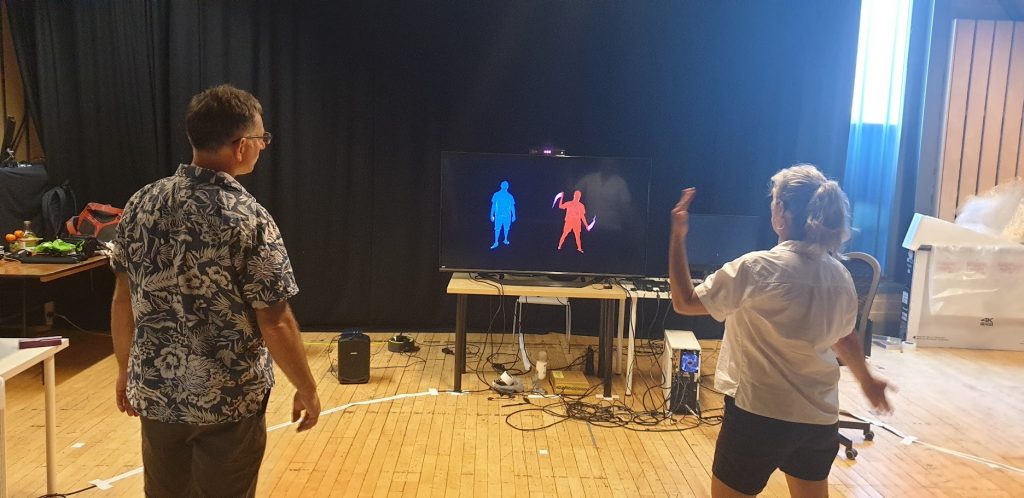

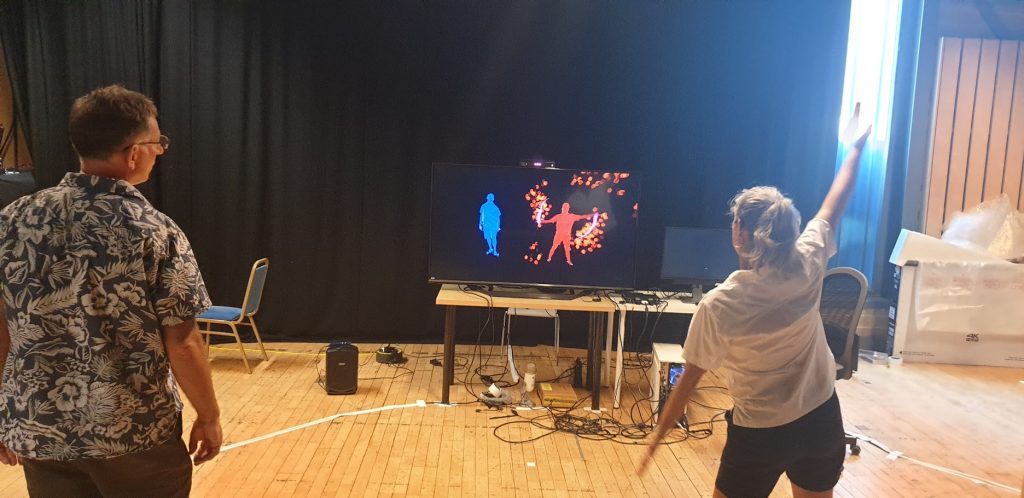

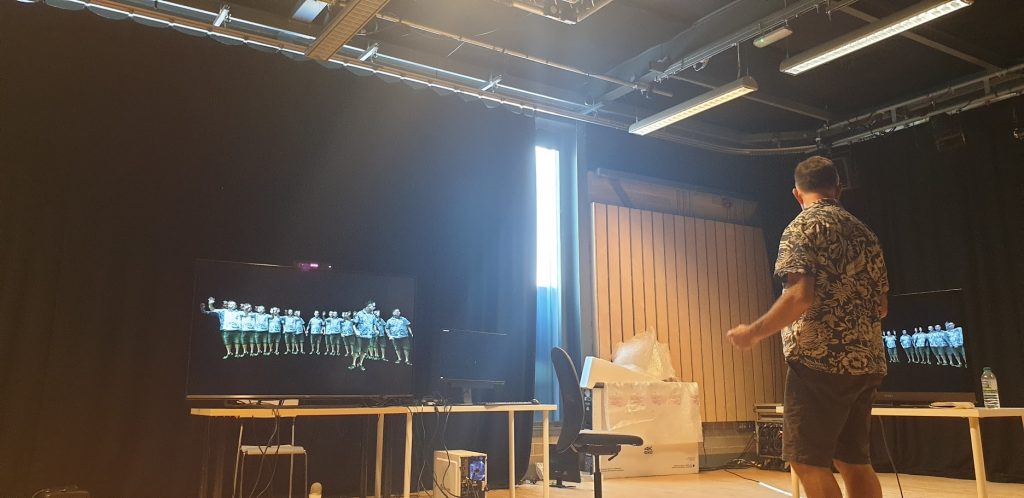

The Suitcase Stories installation facilitates embodied interaction with typographic representations of firsthand accounts of climate change. The work aspires to create a powerful and visceral connection between the participant and individuals affected directly by environmental changes, thus developing greater awareness and propensity towards positive action. Participants interact with powerful and often emotive narratives through upper body movement and gesture, discovering and playing with words and phrases. The entire artwork is integrated within a vintage suitcase, adding aesthetic and thematic dimensions to the user experience. Through this installation, the author sets out to test whether interactive typography, controlled through body tracking, can offer a unique platform for disadvantaged voices to be heard in a powerful and immersive way.

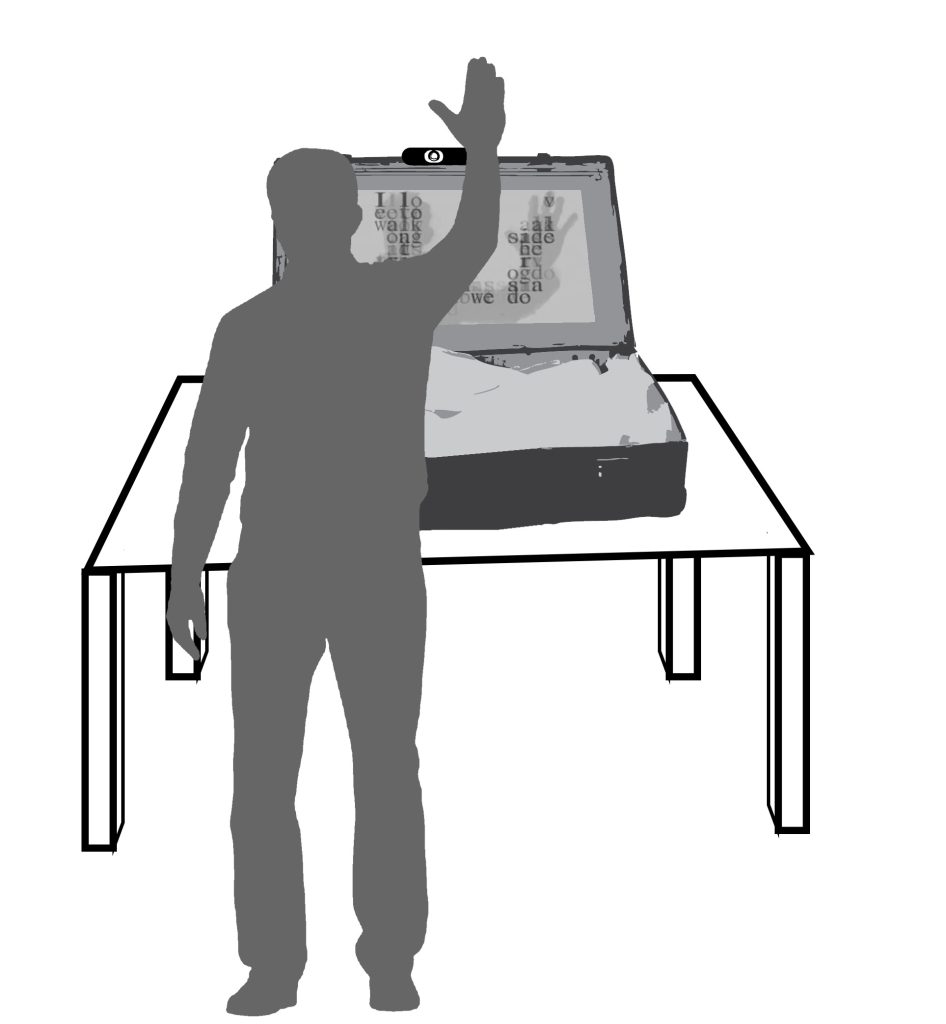

I developed the following lo-fi mock-ups to support the proposal.

Although I had already created bodily-interactive typography some years ago (e.g. Journey Words), this was created using now defunct Quartz Composer patches and recently I have been keen to push the limits of TouchDesigner. So, with just a weekend to create a prototype from scratch in time for the application deadline, I managed to develop the following demo in TouchDesigner.

My proposal was thankfully accepted and I started work in earnest on the installation following the Christmas break. My first task was to find suitable first-hand accounts of climate change that I could legitimately use. After some discourse with organisations such as the Climate and Migration Coalition, it became apparent that several first-hand accounts published by organisations such as Oxfam are already widely shared, with due reference, across media platforms. In the end I re-used and referenced the following accounts:

| 1 | Extract from the account of Marcos Choque, 67-year-old inhabitant of Khapi, in the Bolivian Andes. | Oxfam International. 2009. Bolivia: Climate change, poverty and adaptation. Oxfam International, La Paz, Bolivia. |

| 2 | Extract from the account of Sefya Funge, 38-year-old farmer in Adamii Tulluu-Jido Kombolcha, Ethiopia. | Oxfam International. 2010. The Rain Doesn’t Come on Time Anymore – Poverty, Vulnerability, and Climate Variability in Ethiopia. Oxfam International, Oxford, UK. |

| 3 | Extract from the account of Tulsi Khara, 70-year-old inhabitant of the Sundarbans, in the Ganges delta, India. Quoted in: WWF. 2005. Climate Witness: Tulsi Khara, India. | WWF. 2005. Climate Witness: Tulsi Khara, India. Retrieved from: https://wwf.panda.org/es/?22345/Climate-Witness-Tulsi-Khara-India |

| 4 | Extract from the account of Rosalie Ticala, 33-year-old typhoon survivor of Baganga, Mindanao Island, Philippines. | Thomson Reuters Foundation. 2013. Typhoon survivor Rosalie tells her story in Philippines. Retrieved from: https://news.trust.org/item/20130214164700-xrwmo |

| 5 | Extract from the account of Fatay and Zulaikar, husband and wife of a pastoralist family in Badin district, Sindh, Pakistan. | Quoted in: Climate & Development Knowledge Network. 2012. Disaster-proofing your village before the floods – the case of Sindh, Pakistan. Retrieved from: https://cdkn.org/story/disaster-proofing-your-village-before-the-floods-%25e2%2580%2593-the-case-of-sindh-pakistan |

| 6 | Extract from the account of Assoumane Mahamadou Issifou, NGO employee in Agadez, Nigeria. Gavi, | Quoted in: The Vaccine Alliance. 2023. Ten eyewitness reports from the frontline of climate change and health. Retrieved from: https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/ten-eyewitness-reports-frontline-climate-change-and-health |

| 7 | Extract from the account of Parbati Ghat, 58-year-old community health volunteer in Melauli, Baitadi, Nepal. | Quoted in: BBC Media Action, Living Climate Change. 2024. Mosquitoes in the mountains, Nepal. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/our-work/climate-change-resilience/living-climate-change/nepal-malaria |

| 8 | Extract from the account of Lomilio Ewoi, pastoralist in Kenya. | Quoted in: BBC Media Action, Living Climate Change. 2024. The flood that took everything, Kenya. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediaaction/our-work/climate-change-resilience/living-climate-change/kenya-mental-health |

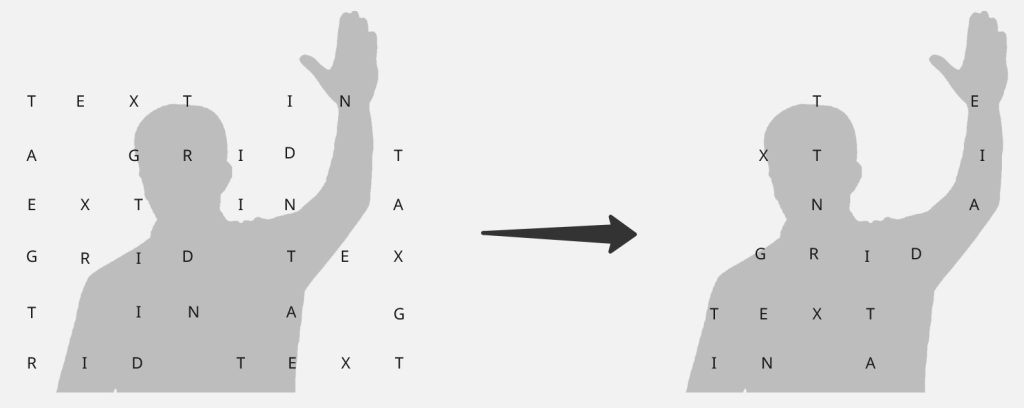

The TouchDesigner development process was quite time-consuming although I managed to achieve an outcome by resolving challenges in key stages. My original demo essentially mixed a Kinetic Typography tutorial by bileam tschepe (elekktronaut) with a 3D Grid with Depth Camera tutorial by Motus Art. This resulted in a grid of letters extruded using depth information provided by a RealSense D345 camera. However, I wanted to only show letters extruded by the body and not those on the background grid, but keeping the left to right flow of text, as shown in the diagram below.

I managed to do this by using a threshold filter to isolate image pixels above a certain greyscale level and therefore considered to be part of the body, and then used this information to reorganise the text indices relating to each grid cell so that text only appeared on cells extruded by the body.

With artistic works featuring typography, there is often a tension between aesthetics and legibility. I wanted participants to enjoy playing with the text, forming ‘word sculptures’ with their bodies, but ultimately they needed to be able to read the text. To this end, I developed a phrase cycling function that sequentially picked out individual phrases when the participant stopped moving and after a short delay, showed them as pure text overlayed along the bottom of the screen. Although it perhaps seemed slightly obvious to do so, I wanted to ensure 100% legibility of these important stories.

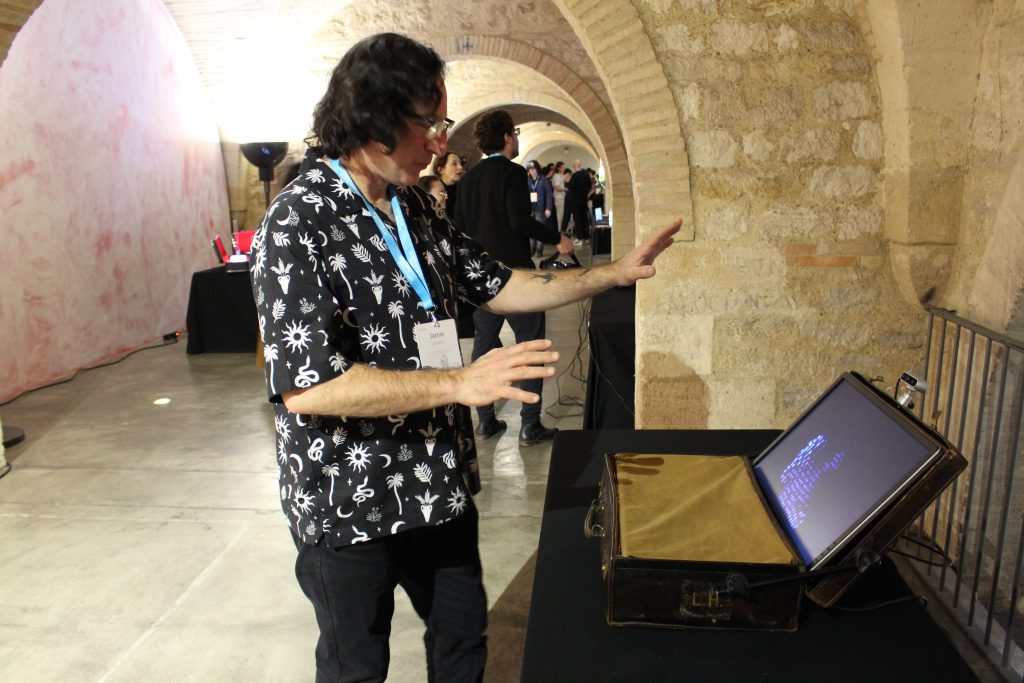

The fabrication side of the project came together quite serendipitously, I found a medium-sized, yet robust, vintage suitcase in an antique bazaar which just happened to be a perfect fit for an old monitor. I used photography mounting components to hold the lid of the suitcase open and support the weight of the monitor, then created a mount for the RealSense camera in the suitcase lid. After several failed attempts trying to get the RealSense camera working with my MacBook (official RealSense support for Mac is discontinued by Intel), I managed to borrow a gaming PC laptop and house that in the body of the suitcase. The last additions were a fan to cool the laptop down and some suitable material to stretch across the interior of the suitcase (which by now had several holes cut into it). You can see the results in the images below.

I had some really useful and insightful feedback from the conference attendees and also a number of productive conversations about using technology to explore human narratives – essentially Digital Humanities. I’m taking a break from this project for a short while to reflect upon where it might go next. In the meantime, if you’re interested in reading the accompanying ACM short paper, you can find it here: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/3689050.3707677

And here is a screen recording demonstrating the phrase selection functionality as it was presented at TEI’25.