I’m currently involved in a collaborative art-tech research project between NUA and Collusion in support of emerging artists in the Norwich and Norfolk area. One of the topics I have been looking into is the way that UX practices and concepts may be used in the context of developing and delivering arts projects. This will come as no surprise, as I am a sometime artist myself as well as being a User Experience Design lecturer at Norwich University of the Arts.

Let’s establish a working definition of UX design as:

A multidisciplinary practice that sets out to create positive experience in the consumption of digital products and services by matching users’ needs, capabilities and motivations with corresponding functionality, content and reward.

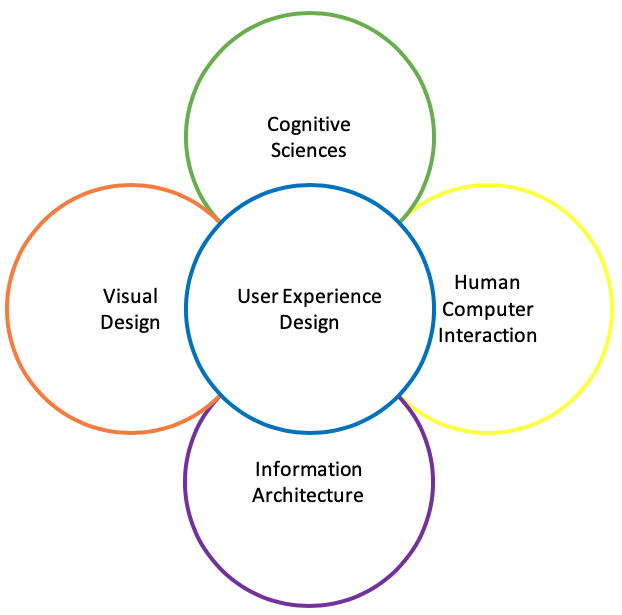

When considering the major areas of contributary practice that feed into UX design as it is commonly thought of, i.e. commercially oriented, it can be seen from the simplified diagram below that at least one or more of these disciplines is likely to be relevant to arts practice. The key questions here are whose art practice, what is the nature of that individual practice and therefore where are the natural synergies between that practice and the hybridised discipline that is UX Design?

The more digital the arts practice and the more it relies upon users, interfaces and content, the closer it comes to the natural territory of commercial UX Design.

Observation #1

Artists operating in the art-tech space would do well to consider where their practice can draw from UX Design and where it needs to be differentiated.

At the risk of stating the obvious:

The further away an arts practice is in nature from commercial UX Design, the more easily an artist can learn, borrow and steal from commercial UX Design.

The closer an arts practice is in nature to commercial UX Design, the harder an artist has to work to differentiate art works from commercial UX design-derived products and services.

Observation #2

Where well-designed user experience is intended to create delight in a commercial context, it can provoke a much wider range of emotional and intellectual responses in an artistic context.

Let’s consider user experience design as a wholistic term that can be applied to the design of both commercial and artistic experiences that involve some form of interface.

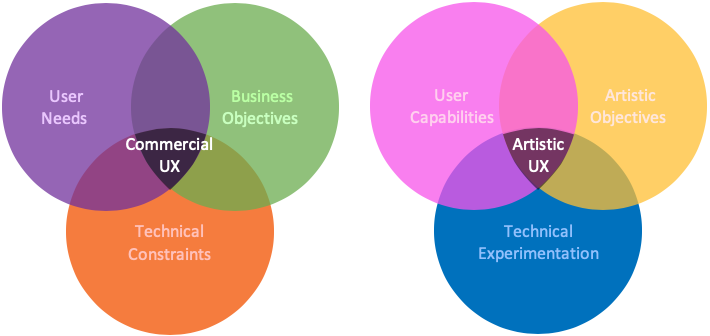

Compare the potential driving forces behind UX for commercial purpose vs. those for artistic endeavour.

If anything, artistic user experience design has more chance of creating delight; it can address whimsical, comedic, bizarre or otherwise engaging non-commercial themes as it is not driven by business objectives. However, delight is not always the response that an artist seeks to provoke. Artistic user experience may reasonably provoke a whole range of responses from shock to shame, anxiety to antipathy etc.

Observation #3

Understand and embrace the research continuum.

In the world of commercial UX, design is underpinned by substantive if not exhaustive research used to develop, evaluate and validate design strategy and implementation. UX research thinking identifies the shifting nature of research activity as a trajectory from formative to summative.

Research cannot be all things at all times, it has a role to play at a given point in a project cycle. Artists would do well to consider how and when they can use research in their projects. For example, thematic exploration at the formative stage of a project to user testing towards a final exhibition / installation.

Observation #4

The designer is not the user, the artist is not the audience.

‘The designer is not the user’ is a common maxim in UX design used to reiterate the importance of objective review and testing. Another well known supposition is that it’s only necessary to test with 5 users in order to identity design problems. This idea comes from an original article published by the grand-daddies of UX Design, the Nielsen-Norman Group.

The 5 user tests approach is based on research identifying that exponentially less new faults are disovered by a greater numbers of testers and therefore 5 testers alone will identify the most pertinent and immediate issues. In a sense, it is a form of cost benefit analysis; why pay for more testers when they will identify far fewer new faults than the first 5? There are many assumptions wrapped up in this assertion, not least that the scale of the project to be tested does not exceed the testing capabilities of 5 individuals. Although the original research is sometimes challenged, in my own opinion, it’s a sensible and achieveable approach to have at least 5 people test the core functionality of a project, be it commercial or artistic. The implication is to expect problems to be found and plan to resolve those problems before re-testing.

Artists woud do well to consider how, when and with how many people they can test their work

Observation #5

Respect the double diamond.

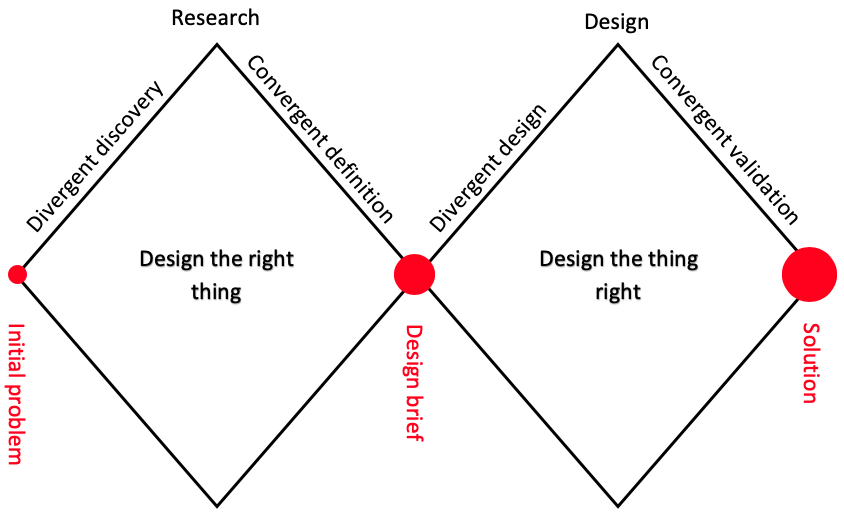

The double diamond is a construct popularised by the Design Council in the mid 2000’s. It has now evolved somewhat and has been adapted to suit a growing number of contexts. It is often used to underpin UX design workflow.

At its heart, quite literally, the double diamond situates a defined design brief. To the left of the design question, the first diamond represents a divergent process that begins with the investigation of an orginal question, problem or proposition.

In the UX design workflow, an initial process of divergent investigation is used to thoroughly explore user needs, behaviours, motivations etc as well as to examine a whole raft of other important contexts such as stakeholder requirements, technological, legal and financial considerations. Through the process of user, stakeholder and domain knowledge discovery, the UX designer can begin to formulate and validate hypotheses and propositions through a convergent process of definition leading towards a validated design brief. The first diamond is often summarised as ‘design the right thing’ and exists to mitigate the risk of creating unnessary and/or unwanted products.

The second diamond is often summarised as ‘designing things right’. It too begins with a divergent phase, but this time the primary activity is to develop a range of designs in reponse to the validated brief. At some stage, the most suitable design is selected and the final approach to an actual solution is characterised as a convergent process of design validation including, of course, user testing.

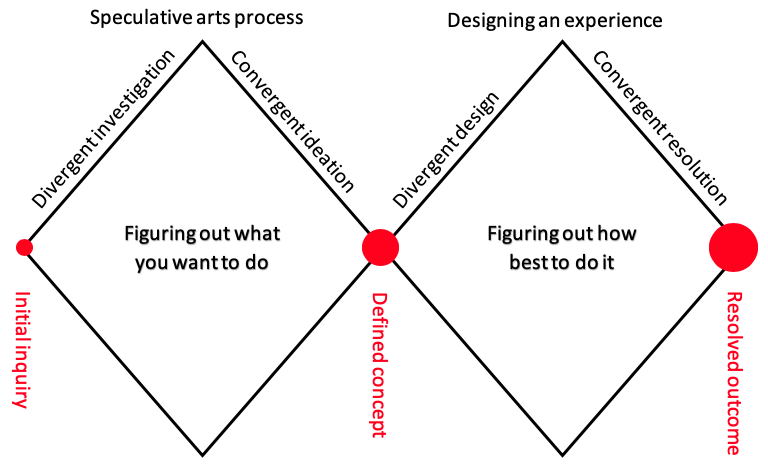

The double diamond approach is exceptionanly versatile and can easily be adapted to the process of making tech-art, as shown below.

In this case, speculative investigation replaces the user / domain knowledge discovery phase, although of course, the artist will discover their own domains of knowledge through the art research process. Convergent ideation replaces design definition with the end result looking very similar – a defined proposition at the heart of the double diamond. The second diamond is perhaps closer to the UX version shown previously; divergent and then convergent processes are used to transform the defined concept into a resolved outcome.

There are a number of other UX design concepts and practices that can easily be appropriated by artists. Check out the following resources to form your own.

Arrango, J., Morville, P. and Rosenfield, L. (2015) Information Architecture, 4th Edition. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media

Cooper, A., Reimann, R., Cronin, D. & Noessel, C. (2014) About Face The Essentials of Interaction Design, 4th Edition. Indianapolis, Indiana: Wiley

Morville, P. (2004) User Experience Design [website] http://semanticstudios.com/user_experience_design/

Schlatter, T. & Levinson, D. (2013) Visual Usability: Principles and Practices for Designing Digital Applications. Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.